Facing an Enemy on Two Fronts- Celebrating More Than 80 Years Since The Tuskegee Airmen Claimed Their Place in History By Photographer and Contributor Steve Tabor

In spite of their desire to do their part for their country, African Americans were forced to take lesser roles in the military until the early 1940’s. This not only pertained to leadership roles, but simpler roles as well. During World War I, African Americans were not allowed to serve as pilots or even observers in aircraft or observation balloons.

One African American, Eugene Bullard, had moved to France prior to the beginning of World War I hoping to escape the prejudice and segregation that existed in the U.S. When the hostilities of war broke out, he enlisted in the French Foreign Legion. Because of his intensity in hand-to-hand combat, Bullard was nicknamed the “Black Swallow of Death.” He was forced off the field of action when he suffered a leg injury.

When Bullard was able to return to action, he became a gunner for the French Air Force and within six months, he was awarded his pilot’s wings and joined the Lafayette Flying Corps (LFC). Existing U.S. War Department policy prohibited Bullard from joining the U.S. flyers. Bullard did not allow this barrier to lessen his desire to fly, and he continued his service under the French flag. During his time with the LFC, Bullard flew twenty combat missions and reconnaissance and pursuit missions. When Bullard left the LFC, he had accumulated fifteen medals for his distinguished service.

Following the war there were a number of surplus and new aircraft available for purchase and like their white counterparts, many African American males and females were inspired to take to the skies. For white flyers, there were several flying schools offering opportunities for them to gain their civilian pilot’s license. But, for African Americans, the pursuit of acquiring a civilian pilot’s license was a test of patience and in some cases, a test of their pocketbook. It was extremely difficult to find a school that would actually accept an African American candidate.

In the case of sixteen-year-old Chauncey Spencer, he and his father approached the Manager of the Preston Glenn Airport in Lynchburg, Virginia, now known as the Lynchburg Regional Airport. When Spencer told the Manager of his desire to receive flight instruction, the Manager told him that they would not allow “Negros” to attend the school because they do not have the intelligence.

Charles Alfred Anderson, Sr. from Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, was accepted to a flight school with the stipulation that he purchase his own plane prior to beginning his flying lessons. Anderson estimated that he spent $6,000 over a four-year period in order to secure his commercial pilot’s license.

Many African Americans, especially those who could not afford to purchase their own aircraft, found themselves in and around the City of Chicago as word spread that there may some flight schools were willing to accept African American candidates.

Two such individuals were Cornelius Coffey and John Robinson. In 1931 Coffey and Robinson found themselves working as auto mechanics at a Chicago car dealership. Coffey and Robinson applied to the Curtiss-Wright School of Aviation in Chicago to train as aviation mechanics. Coffey and Robinson were initially accepted to the program, but when the school discovered Coffey and Robinson were African American, they refused to grant admission to the two candidates. When the owner of the car dealership, Emil Mack, found out about the problem his two employees were having, he stepped in and threatened a lawsuit against the school. Eventually, the school withdrew their denial, and they admitted Coffey and Robinson. After a two-year period, Coffey and Robinson completed their training and earned their commercial pilot’s licenses. The achievements of Coffey and Robinson are viewed as groundbreaking in the history of African American aviation.

Following their time at the Curtiss-Wright Flying School, Coffey, Robinson and other flyers organized the Challengers Air Pilots’ Association (CAPA) in an effort to expanded flying opportunities for African Americans. The only problem was African American were excluded from Chicago area airfields, and the CAPA established their own airfield in Robbins, Illinois.

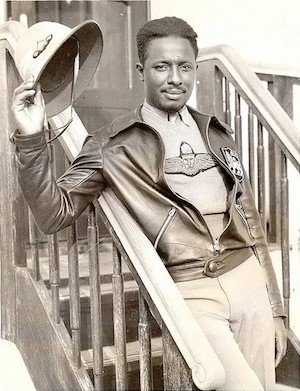

With his experience in forming an all-African American aviation unit in the Illinois National Guard, Robinson’s reputation spread in the aviation community. In 1935, Robinson accepted the invitation of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, to serve as an officer in the Imperial Ethiopian Air Force during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. Robinson’s contributions in the war were documented by national news outlets as well as the Chicago Defender. These reports are credited with highlighting the desires of many African Americans to serve in the U.S. Army Air Corps (USAAC). Not only is Robinson credited with creating Tuskegee Institute’s flight program which taught a significant portion of the African American pilots, Robinson is often referred to as the “Father of the Tuskegee Airmen.”

With his commercial pilot’s license, Coffey along with his wife, Willa Brown, also an accomplished and recognized pilot, launched the Coffey School of Aeronautics at Harlem Airport on Chicago’s Southside. Coffey soon began teaching African Americans how fly. It was when his students reached their competency level to qualify for their pilot’s license that they ran into another obstacle. Because of Coffey’s African American background, his flight school could not issue pilot’s licenses to his students. C.C. Moseley, owner and operator of the Curtis-Wright Technical Institute, offered Coffey the opportunity to use his flight school as the issuing authority for Coffey’s students.

It was in 1934, when Coffey’s School of Aeronautics quietly became part of aviation history. After being denied admission to a flight school in Lynchburg, Virginia, Spencer continued to dream of acquiring his pilot’s license and found himself at the steps of the Chicago Aeronautical University. Spencer was discouraged by the school administrators from attending the school because the classes were made up of all white students. After giving the school’s administrators a hundred-dollar deposit, Spencer convinced them to allow him to attend classes. The following day, within two hours of beginning his classes, Spencer was summoned to the school’s office and was told that students objected to his attendance, and he would not be allowed to return. The administrator urged Spencer to attend Coffey’s aviation school.

Needing funds to pay for his twenty-five dollars an hour flight lessons, Spencer took a job dishwashing. Eventually Spencer earned his pilot’s license, but repeatedly heard from others, “You’ll never get a job flying.” Spencer knew that no one was willing to hire an African American pilot, including the USAAC, but this did little to discourage him from following his dream.

At the same time, the winds of war were stirring in Europe, U.S. military officials saw that Germany was developing a powerful presence over the skies of Europe and knew that this conflict or other future conflicts could not be won without establishing a significant presence in the air. Although the U.S. had some white males with their civilian pilot’s licenses who would be able to serve as pilots in the USAAC, political and military officials knew the U.S. could not match the number of and skill levels of the pilots already part of the German Luftwaffe. To close this gap, in 1938, General Henry “Hap” Arnold approached Oliver Parks of Parks Air College, C.C. Moseley of the Curtiss-Wright Technical Institute, and Theophilus Lee, Jr. of the Boeing School of Aeronautics to voluntarily create pilot training schools which would become the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP). The goal was simple, the CPTP would increase the number of white civilian pilots who would be able to join the USAAC, if the U.S. joined in the battle against the German war machine.

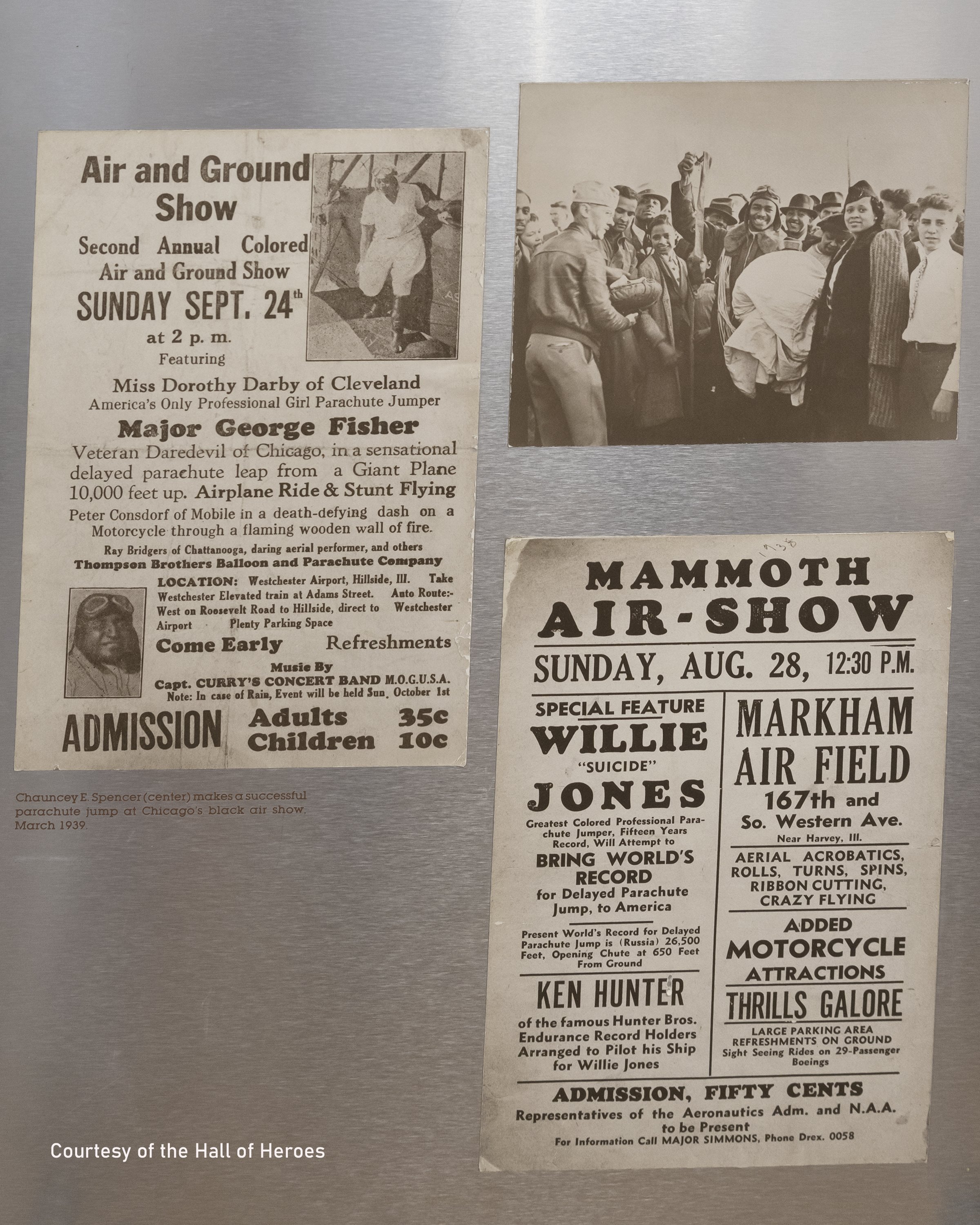

For African Americans interested in serving our nation as aviators, it was a vastly different story. Not only had the armed forces not changed their policy towards allowing African American to serve as pilots, but in a 1925 Memorandum to the Chief of Staff regarding the “Employment of Negro Man Power in War” issued by U.S. Army Commandant, H.E. Ely, dealt the dreams of African American aviators an almost fatal blow. The Memorandum insisted the “study” indicated that African American males have not developed “leadership qualities” and “His mental inferiority and inherent weakness of his character are factors that must be considered with great care in the preparation of any plan for his employment in war.” The Memorandum further detailed that approximately 200,000 African American males should be mobilized in a battalion assigned to the National Guard and U.S. Army. Maintaining current segregation practices, commonly referred to as “Jim Crow,” the battalion would be housed and trained separately from white soldiers and commanded by white officers, but African American lieutenants could be assigned to the battalion along with white lieutenants. Discouraged about the prospects of becoming a military aviator, Spencer and other African American pilots were anxious to prove their aviation capabilities and, like their white counterparts, be able to employ their skills to defend our nation when and if the opportunity arose. To raise the public awareness about the skills and talents of African American aviators, the flyers formed the National Airmen’s Association of America (NAAA).

Their initial endeavors were airshows at Chicago’s Harlem Airport. The crowds were entertained by stunt flying and what is called parachute races, where participants jumped out of a plane from 10,000 feet and raced to the ground by delaying the amount of time they opened their parachutes.

The success of the airshows led Spencer and fellow pilot, Dale White, to attempt a ten-city tour that would be featured in the Chicago Defender, an African American community newspaper. Plans called for the two pilots to conduct an aerial performance at each stop before progressing to their next scheduled stop. The tour was scheduled to end in Washington, D.C. where Spencer and White would attempt to meet with and urge Congressional representatives to push for the inclusion of African Americans in the USAAC. The flight expenses would be covered by brothers Ed and George Jones, who generated their wealth through running numbers games in Chicago, and who were commonly referred to as the Jones brothers. Spencer also invested $500, which allowed Spencer and Dale to purchase a well-used Lincoln Paige biplane for $1,500.

After completing their preparations, Spencer and Dale took to the skies above Harlem Airport. Approximately three hours into their cross-country flight, they met with a mid-air emergency when the plane’s crankshaft broke, and they were forced to land in a farmer’s backyard in Sherwood, Ohio. It took them two days to complete the repairs before continuing on their journey.

After completing their preparations, Spencer and Dale took to the skies above Harlem Airport. Approximately three hours into their cross-country flight, they met with a mid-air emergency when the plane’s crankshaft broke, and they were forced to land in a farmer’s backyard in Sherwood, Ohio. It took them two days to complete the repairs before continuing on their journey.

On their final leg before reaching Washington, D.C., they planned on landing at Morgantown, West Virginia airport. However, while enroute, they learned that the airport was closed and they needed to divert to Allegheny Airport in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Arriving after nightfall, the airport did not have a lighted runway. Fortunately, there was a commercial plane just ahead of them that they were able to follow and safely reach the ground. Due to their actions, they were required to meet with an inspector from the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA), predecessor of the Federal Aeronautics Administration (FAA). After listening to their story, the inspector cleared Spencer and White and allowed them to retake to the skies.

Members of the Pittsburgh Courier, an African American owned newspaper, learned Spencer and White were at the airport and met with them prior to their departure. The newspaper’s publisher, Robert Vann, gave Spencer and White five hundred dollars and letters to influential members of Congress. After leaving Pittsburgh, they landed at Washington Airport and were met by members of the African American press and Edgar Brown, lobbyist for the NAAA and the Negro Federal Employees Union.

Following their arrival, Brown took Spencer and White to visit several officials who indicated their support. Brown took the pair on the underground train which connects the Capitol and Congressional offices. As the trio was exiting their electric car, they met the junior Senator from Missouri, Harry S. Truman, walking down the corridor. Brown did not miss a step and introduced Spencer and White to Truman. Always direct and to the point, Truman asked them, “Why are they in Washington?” Spencer and White indicated that they had taken time off their Work Progress Administration (WPA) jobs to come to Washington to dramatize the need for African American pilots in the USAAC.

Truman was genuinely surprised to learn from Spencer and White that African Americans were not allowed to fly in the USAAC. They asked for Truman’s assistance to open the door for them and their fellow African American pilots because they had not been able to do so on their own. Before the conversation concluded, Truman agreed to meet the pair at their plane later that afternoon.

When Truman arrived at their plane, he could not imagine that they had flown such a distance in an airplane in such poor condition. Truman asked the pair several background questions about themselves and their plane, but when asked if he wanted to take a flight, he declined a ride. According to Spencer, Truman said to the pair that if we had the guts to fly this thing to Washington, he’d have the guts to back their request.

Before leaving Washington, Spencer and White met with other Congressional members. One of the members meeting with the pair was Everett Dirksen, who introduced an amendment to the Civil Aeronautics bill in the House of Representatives. Three years later the bill passed, and African American aviators were allowed to become pilots in the USAAC.

Public Law 18 (PL18) was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on April 3, 1939. PL18, expanded the CPTPs to include African American pilots in the USAAC and establish training programs at West Virginia State College, Tuskegee Institute, Hampton Institute, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University and Delaware State College. The Coffey School of Aeronautics also became a CPTP training site. The newly established sites would remain racially segregated. In military circles, this became known as the “Tuskegee Experiment.”

The War Department established standards for African American candidates that ensured that only the most able and intelligent candidates could be accepted. Psychological units used standardized tests, dexterity and leadership qualities to select candidates from pilots, navigators, and bombardiers. The War Department determine that they would only accept candidates with a level of flight experience or completed a higher education level.

Coleman Young, former Tuskegee Airmen and who later became the Mayor of the City of Detroit stated, “They made the standards so high, we actually became an elite group. We were screened and super-screened. We were unquestionably the brightest and most physically fit young Blacks in the country.”

Approximately five months after the opening of the Tuskegee Institute, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the campus. During her visit she took a half an hour flight with Chief Civilian Flight Instructor, C. Alfred Anderson. Following the flight, Roosevelt exclaimed, “Well, you can fly all right.”

After returning to Washington, D.C., Mrs. Roosevelt leveraged her position as a trustee of the Julius Rosenwald Fund to secure a loan to assist with financing the construction of Moton Field at Tuskegee Institute.

With the CPTP in place the USAAC, which was renamed U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF), finally had enough qualified candidates to create a squadron of African American flyers and support personnel. On January 16, 1941, the War Department announced the creation of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, later known as the 99th Fighter Squadron.

A white officer, Captain Harold Maddux was assigned to command the 99th Squadron, a group of 271 enlisted men assigned to Chanute Field in Rantoul, Illinois. During their time at Chanute Field five African American enlisted men were admitted to Officers Training School (OTS). The five candidates, Nelson Brooks, Elmer Jones, James Johnson, Dudley Stevenson, and William Thompson, successfully completed their training and received their commissions as the first African American officers in the USAAF.

When the group of African American enlisted men needed further training, they were transferred to Alabama for further training. However, due to the small number of African American enlisted personnel during their period of advanced training they were integrated with white enlisted personnel.

In June of 1941, the 99th Fighter Squadron began to take shape. The initial compliment consisted of 47 both White and African American officers and 429 lower ranking men. The initial class of thirteen pilot candidates performed their preliminary training at Moton Field and advanced training was conducted at Tuskegee Army Airfield.

After returning to Washington, D.C., Mrs. Roosevelt leveraged her position as a trustee of the Julius Rosenwald Fund to secure a loan to assist with financing the construction of Moton Field at Tuskegee Institute.

With the CPTP in place the USAAC, which was renamed U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF), finally had enough qualified candidates to create a squadron of African American flyers and support personnel. On January 16, 1941, the War Department announced the creation of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, later known as the 99th Fighter Squadron.

A white officer, Captain Harold Maddux was assigned to command the 99th Squadron, a group of 271 enlisted men assigned to Chanute Field in Rantoul, Illinois. During their time at Chanute Field five African American enlisted men were admitted to Officers Training School (OTS). The five candidates, Nelson Brooks, Elmer Jones, James Johnson, Dudley Stevenson, and William Thompson, successfully completed their training and received their commissions as the first African American officers in the USAAF.

When the group of African American enlisted men needed further training, they were transferred to Alabama for further training. However, due to the small number of African American enlisted personnel during their period of advanced training they were integrated with white enlisted personnel.

In June of 1941, the 99th Fighter Squadron began to take shape. The initial compliment consisted of 47 both White and African American officers and 429 lower ranking men. The initial class of thirteen pilot candidates performed their preliminary training at Moton Field and advanced training was conducted at Tuskegee Army Airfield.

The 99 th was placed under the direct command of Captain Benjamin O. Davis, one of two African American officers serving in the U.S. Army. The Tuskegee Army Airfield was under the command of white officers. Major James Ellison was the first commanding officer, but he was transferred in January 1942 because of his assertion that the African American sentries and military police had authority over the white citizens living in the vicinity of the airfield. Colonel Frederick Von Kimble succeeded Ellison, but he faced criticism and resentment from his charges because of his adherence to segregation policies which were contrary to recently established Army regulations. Major Noel Parrish replaced Von Kimble and credited with his open-minded approach, he seemed better suited to meeting the demands of hiscommand.

Among Parrish’s priorities were to improve the relations between the civilian community living near the Airfield and base personnel. Additionally, he sought to improve the living conditions at the Tuskegee Army Airfield by ending the segregation policy establish by his predecessor, reducing the overcrowded conditions on the base and took steps to improving the overall morale among his troops.

Among Parrish’s highest accomplishments was his demand for high performance standards from his white and African American charges. Parrish placed high regard on professionalism and character regardless of race or ethnic background. Through his leadership Parrish is credited with disproving many of the accusations published in the 1925 memo. Given the opportunities Parrish and members of the 99th proved that African Americans could perform to a high level in combat and leadership situations.

Parrish so strongly believed in the abilities of the Tuskegee pilots and their ground support personnel that despite his critics, including General Henry “Hap” Arnold, he constantly fought for his men to be included in the U.S. war effort.

The 99th Fighter Squadron was deemed ready for combat in April 1943. Because the squadron had such a small number of personnel, they were assigned to be part of the 33rd Fighter Group. Due to Army policy their North Africa base remained segregated. The segregation practice failed to allow the inexperienced flyers in the 99th the opportunity gain from the knowledge and experiences of their white battle-experienced counterparts.

Shortly after arriving in North Africa and flying P-40 Warhawks, the 99th flew their first combat mission to attack the island of Pantelleria in the Mediterranean Sea in preparation for an Allied invasion of Sicily. The mission proved to be highly successful and contributed to Allied movement into southern Italy. The 99th was transferred to Sicily and awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC) for their performance in combat.

Despite the performance of the 99th in North Africa, the Commanding Officer of the 33rd Fighter Group, Colonel William Momyer, reported to North African Air Forces Commander, Major General John Cannon, that the 99th was ineffective in combat. Momyer cited that the pilots were cowardly, incompetent, or worse. Time Magazine got wind of the report and published an article regarding the communication which resulted in an Armed Services Committee hearing to determine if the “Tuskegee Experiment” should be concluded.

Arguments against the Airmen included their inexperience in air-to-air combat, and the resurfacing of assertions of their low intelligence and inability to handle complex situations. Colonel Davis, Jr. argued in support of the 99th, but it was Colonel Emmett O’Donnell that prevented the recommendation of disbanding the 99th from moving forward to President Roosevelt.

In an effort to provide actual proof of their performance, General Arnold, once a critic of the Tuskegee Airmen, ordered an evaluation of all units flying P-40’s in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations to determine the effectiveness of the 99th. The evaluation concluded that the 99th’s performance was at least equal to other units flying the same aircraft in the Mediterranean Theater.

The 99th continued its presence in the Mediterranean to support the Allied invasion of Italy. They were tasked with providing air support for the U.S. Fifth Army’s invasions on Foggia and Anzio. Following the invasion of Anzio, German forces launched a counter offensive that included Luftwaffe raids using their Focke-Wulf (Fw) 190 Shrike fighter bombers. The 99th along with seven other fighter squadrons defended the advance by downing thirty-two enemy aircraft. The 99th’s total of thirteen downed aircraft was the most of any group involved in the action.

The 99th earned their second DUC for their support of French and Polish forces during their assaults on Monastery Hill near Monte Cassino. While German forces held the position, the 99th provided ground support operations which allowed ground troops to overtake and force the surrender of German forces.

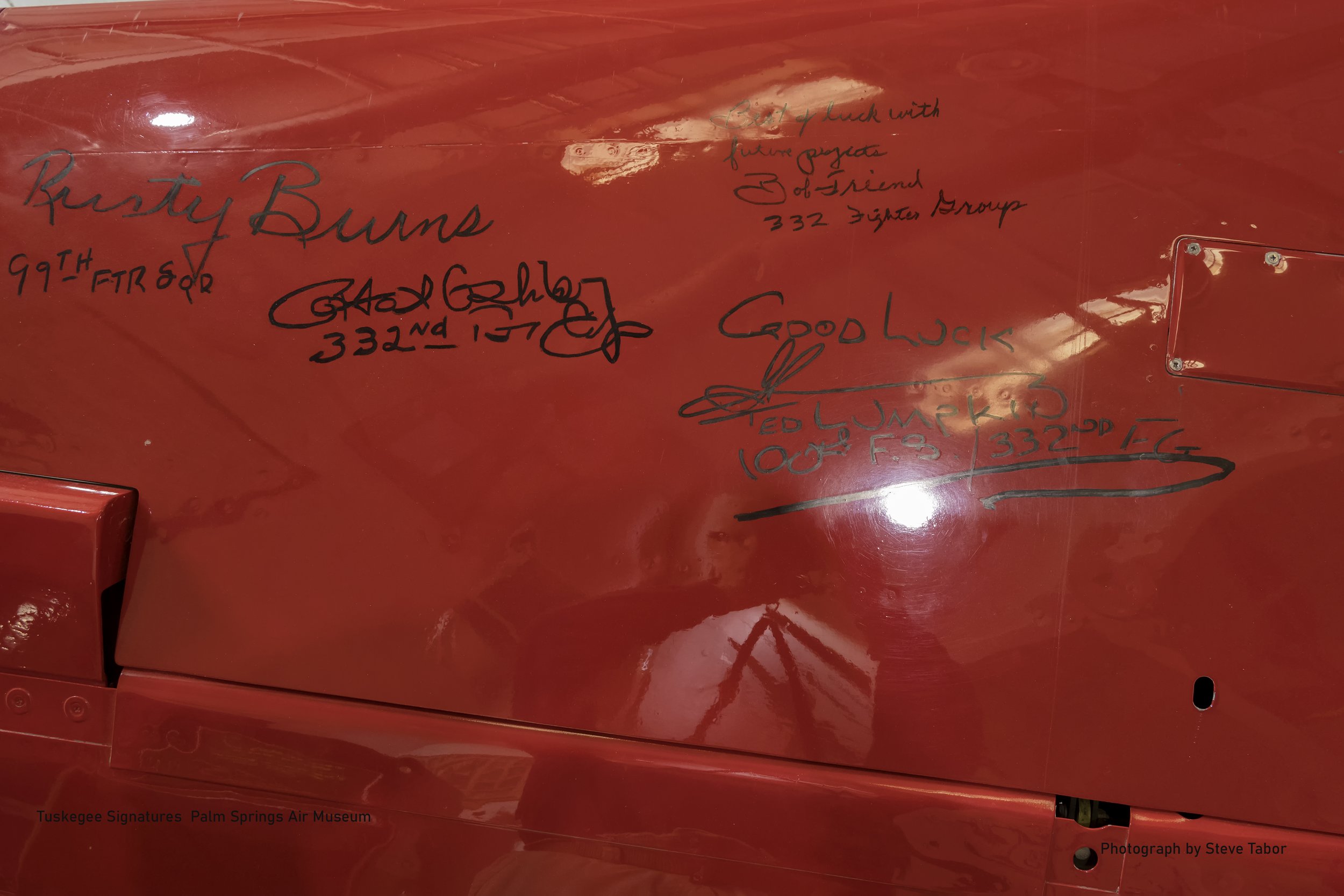

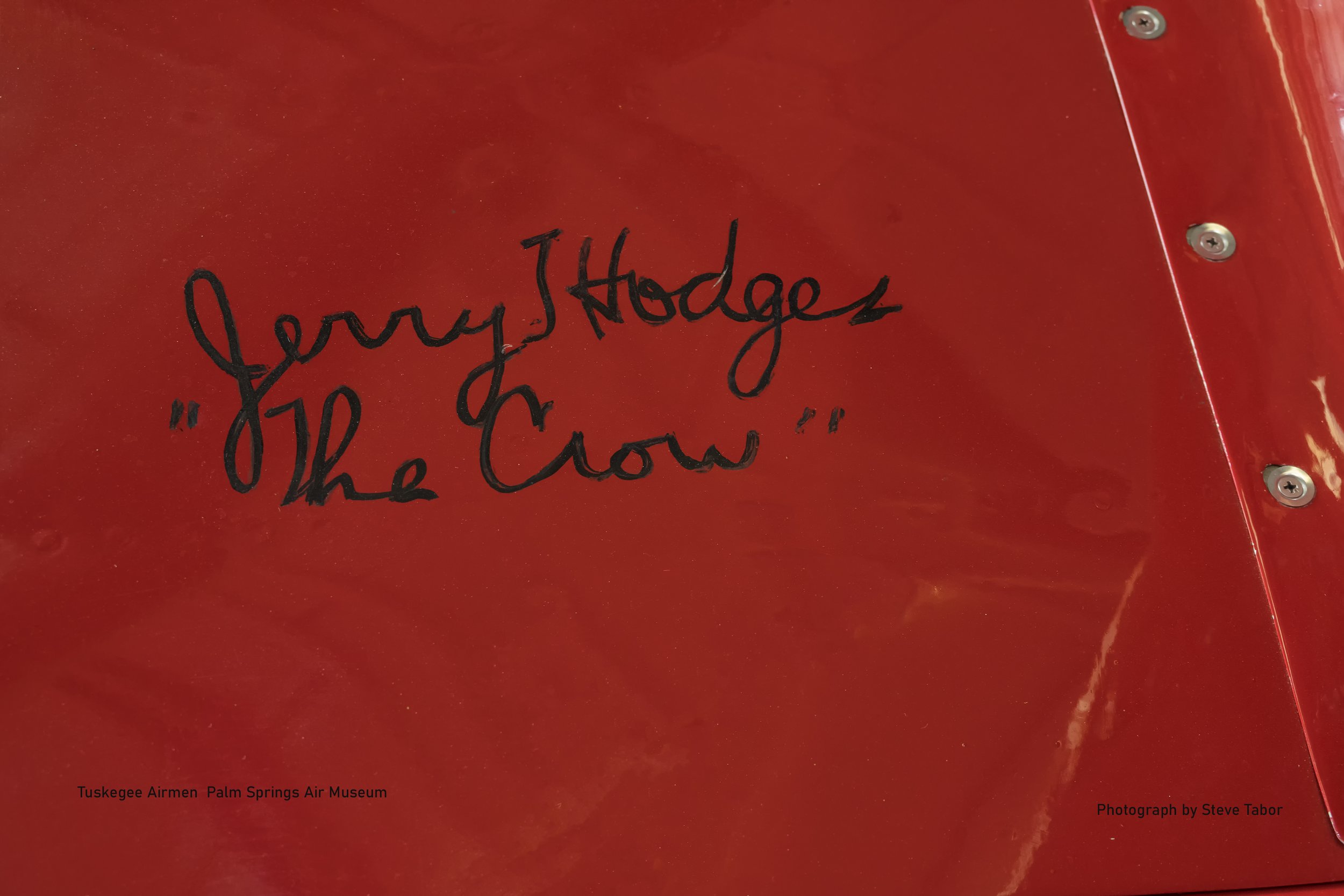

In February 1944, the number of Tuskegee Airmen grew large enough to accommodate the formation of the 332nd Fighter Group composed of three new fighter groups: 100th; 301st; and 302nd. The 99th later joined the 332nd Fighter Group that May. Based at Ramitelli Airfield near the Italian City of Campomarino, the Fighter Group was assigned to escort the heavy bombers, B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators, of the Fifteenth Air Force. These are the missions where the Tuskegee Airmen became legends of the skies.

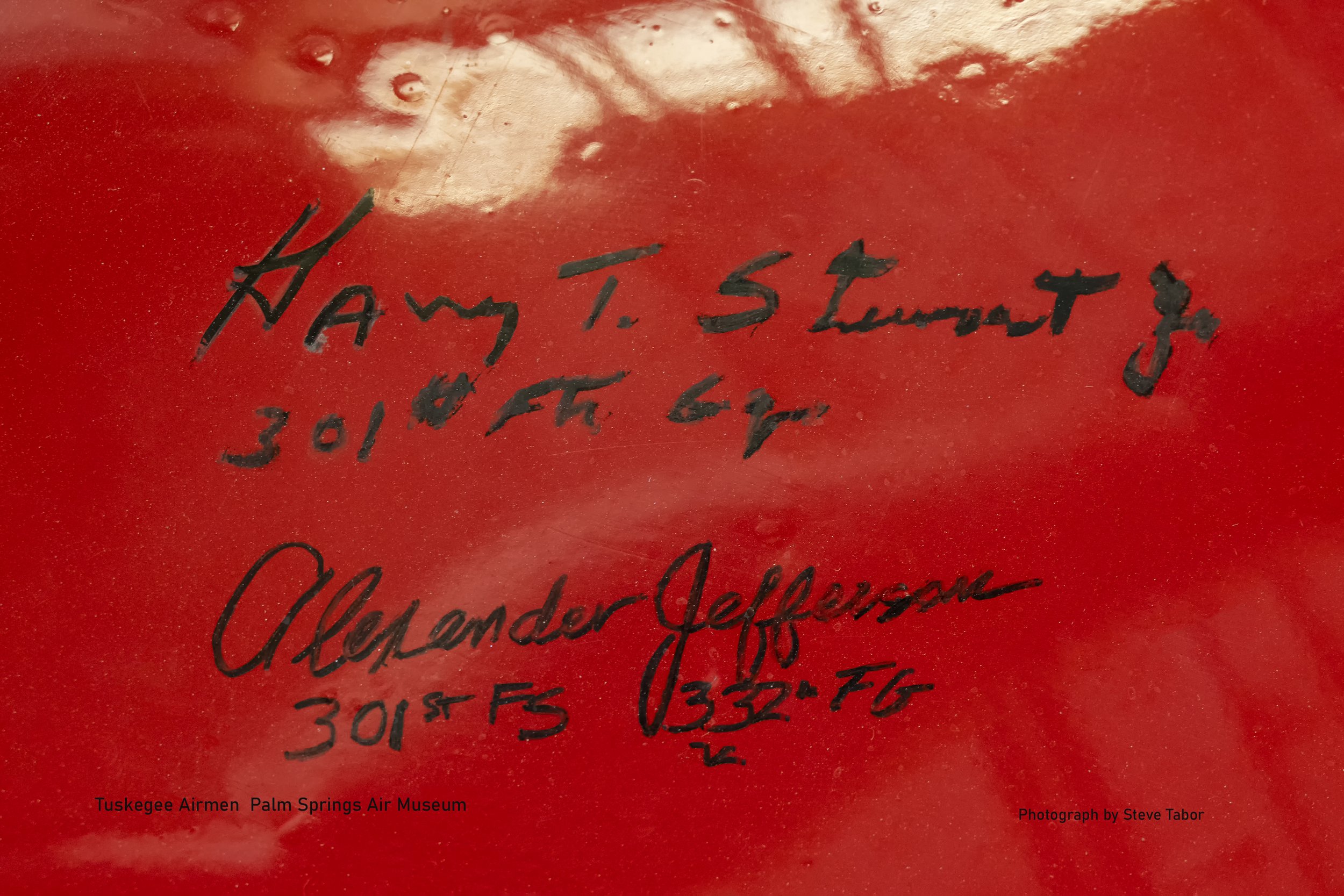

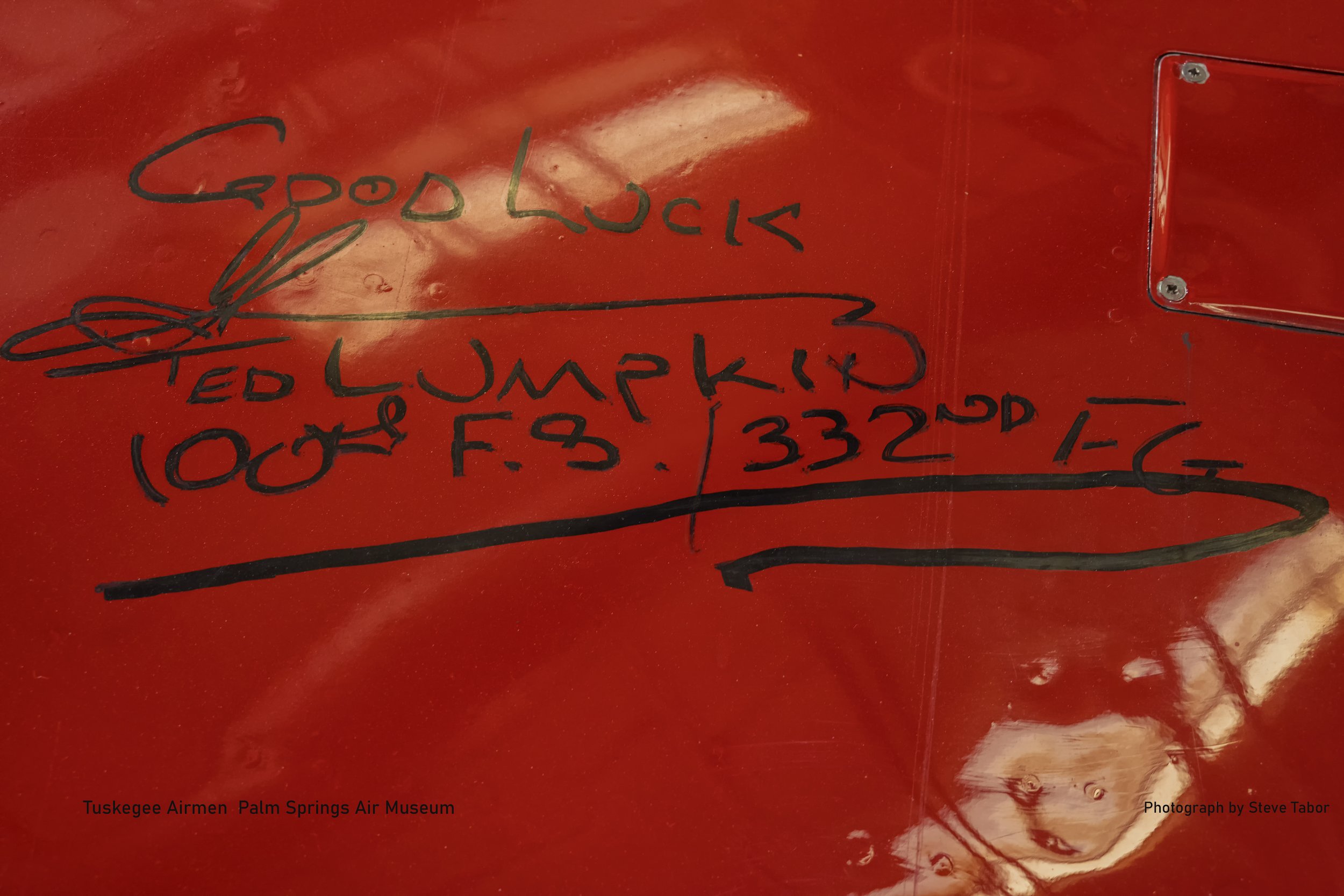

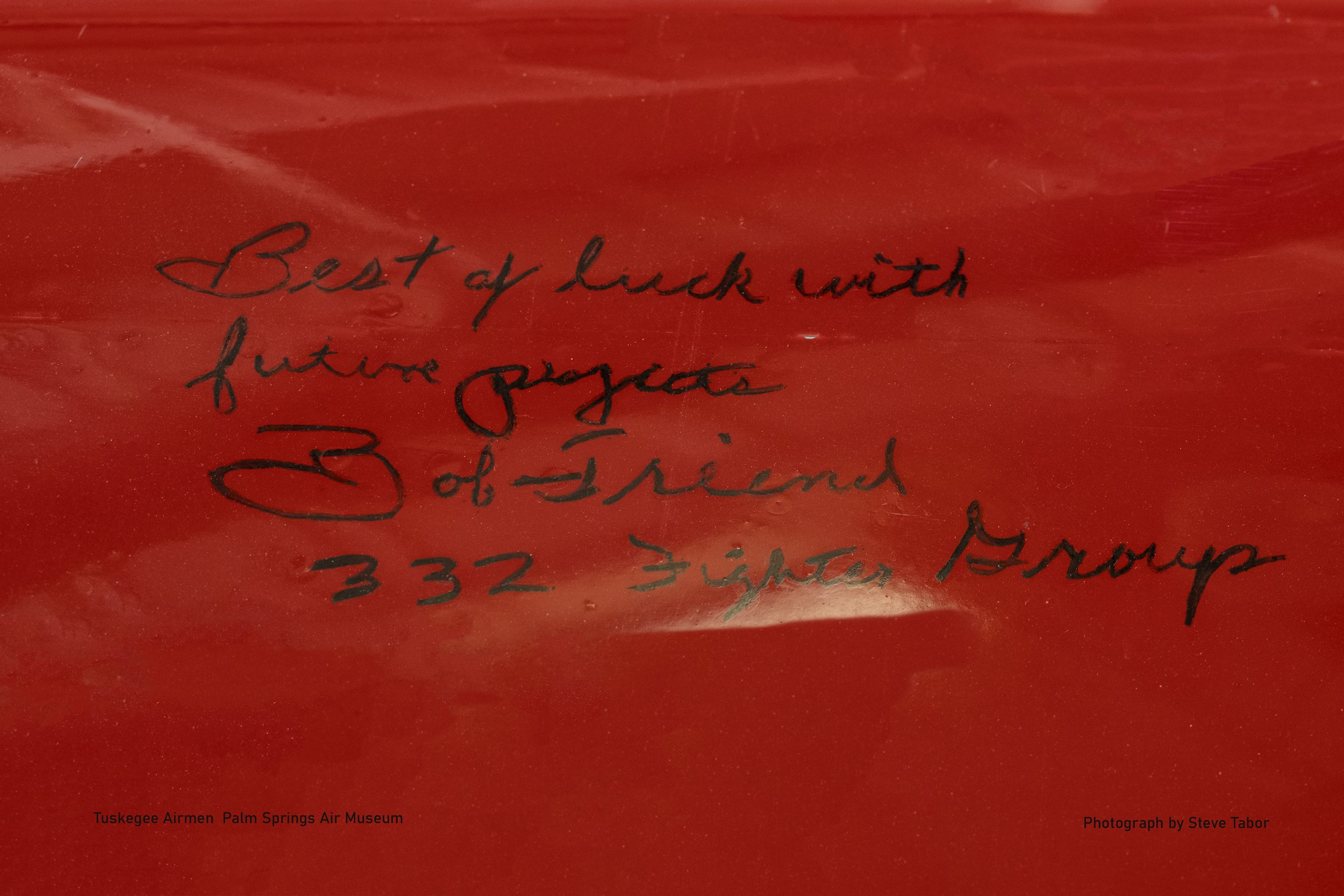

At this time, most of the pilots from the 332nd were flying P-47 Thunderbolts and P-51 Mustangs, and their new distinctive paint scheme cemented their nickname of “Red Tails” in aviation history. Like other flying groups, each group had their own paint scheme or design on some portion of their aircraft. For the Tuskegee Airmen, their planes already displayed a red propeller spinner, so they added red paint to the aircraft’s vertical stabilizer (tail), horizontal stabilizers (rear wings), and a set of yellow and red stripes on their wings. The red tail clearly distinguished them from other fighter groups.

From Ramitelli, the 332nd could provide air support for the heavy bombers flying missions into Axis held regions such as Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, Poland, and Germany. Initially, the bomber crews of the Fifteenth Air Force suffered heavy losses as they entered the highly fortified skies above their targets. In addition to heavy anti-aircraft gunfire, the bombers encountered skies filled with a variety of fast and maneuverable German fighters that could easily dart in and out of the slow-moving bomber formations. The gunners positioned at various locations inside the plane could not match the defenses of the German forces. Knowing that attacking these targets by air was the most effective way to advance Allied forces, however, they could not continue to accumulate the heavy losses bombers and crews, USAAF officials new that they needed to include the use of fighter escorts throughout the bombing mission to combat the German fighters.

The change in strategy brought the abilities and skills of the Tuskegee Airmen to light. On one such mission in March 1945, seventeen bombers from the Fifteenth Air Force were slated to fly to Berlin hoping to destroy a Daimler-Benz tank factory. The heavily defended route to Berlin included the usual complement of heavy anti-aircraft guns and the Fw 190’s, but this time the Luftwaffe added the Messerschmitt (Me) 163 Komet, a rocket powered fighter, and twenty-five Me 262’s Swallow, Germany’s new jet fighter. By the time the aircraft returned to their base, Charles Brantley, Roscoe Brown, and Earl Lane had shot down three of Me 262 jets.

The 332nd has been credited with not losing any of the bombers they were called to escort. Approximately 2005, Alan Gropman, a professor at National Defense University, reviewed more than 200 mission reports by Tuskegee Airmen. Gropman states that based on those reports, he could not find any evidence of bombers lost during their escort missions. However, Dr. Daniel Haulman, a military historian, states that between 2006 and 2007 he reviewed mission reports filed by Tuskegee Airmen, bomber pilots, missing crew reports and witness testimony. From his research, Dr. Haulman reports that 25 bombers were shot down by enemy fighter aircraft while being escorted by the Tuskegee Airman. In his later research, he claims at total of 27 bombers were lost during the 332nd escorts. Despite Haulman’s research, the 332nd’s impressive record represents a substantial decrease in the number of lost aircraft over the European skies and certainly expedited the Allies advances into Berlin.

With the success of the 332nd Fighter Group, the USAAF fell under pressure from civil rights organizations to do away with the established quota limiting the number of 100 African American aviator trainees at any one time and no more than a total of 200 trainees per year. In May 1943, the 616th Bombardment Group was formed. Due to the limited number African American crew members available, the 616th was assigned to fly with the all-white 477th Bombardment Group. During the four-month training period the 477th had to be deactivated because of the number of cadets that did not meet the established training standards.

By January 1944, the 477th had enough African American pilots and crew members to be re-established the 477th as an all-African American unit. Eventually the 477th grew to include four bombardment groups: the 616th, the 617th, the 618th, and the 619th. The 477th was assigned to fly the B-25 Mitchell Bomber, a twin engine medium bomber that made its reputation from the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo in April 1942.

Securing enough pilots to form the 477th Bombardment Group was not a concern for the USAAF. They had an ample supply of pilot candidates due to their pilot training program at Tuskegee and the number of pilots who flew with the fighter squadrons in the Mediterranean and Europe. However, because of the B-25’s twin engine configuration, previously trained pilots as well as novice pilots needed to receive multi-engine training. Their initial training was at Tuskegee. Upon successful completion of that they were given advanced training at Mather Field near Sacramento, California.

The B-25’s required a crew member to serve as a bombardier-navigator. At the time, the USAAF did not have any of these schools in operation for African American candidates. Eventually, these crew members were sent to Hondo Army Air Field and Midland Air Field in Texas and others were sent to Roswell, New Mexico.

Gunners and ground crew were the final positions necessary to support the operation of the B-25. Gunnery school was conducted at Eglin Field near Valparaiso, Florida. Ground crews received their initial training at Mather Field and their advanced training in Inglewood, California, near the North American Aviation B-25 factory.

Depending on their training schedules, the various crew members would reunite at Selfridge Air Field Airfield near Detroit, Michigan when they completed their training assignments. Once there, they received their crew assignments for their final training exercises before being deployed to the European theater. Initially, it was projected that crews would begin their combat assignments in November 1944. However, their deployment would not materialize because of their lack of skills or training, but because of the actions of their commanding officer, Colonel Robert Selway.

Prior to and during the assignment of 616th, Selway used the 477th to promote many of the white aviators in his group. When members of the 616th arrived, Selway made no effort to hide his prejudice against the African American airmen. He refused to socialize with them, strongly discouraged the other white officers in the squadron from doing so as well, and maintained strict segregation practices on the base. In May 1944, without any prior warning, Selway ordered the African American members and their white superior officers of the 477th to board trains and transferred them to a smaller and less equipped base, Godman Air Field, near Fort Knox, Kentucky. This transfer severely impacted their final training opportunities. Godman was considerably smaller than Selfridge in acreage, aviation fuel supplies, the number of runways, and hanger space. Additionally, Godman’s geographic location had a negative impact on overall flying conditions. As a result, the move substantially delayed crew training and dealt a severe blow to the airmen’s morale.

Throughout their assignment period the 477th was drastically understaffed, and Selway did little to improve the situation. From the period between February 1944 to January 1945, the unit was not fully staffed at every position, and the bombardiers were never fully trained. Despite consistently proving their level of expertise, crews repeatedly engaged in competency level training missions instead of advancing to combat training. By the time the unit left Godman, crews accumulated 17,875 flight hours and were involved on only two minor accidents. Neither accident was attributed to crew error and the unit was commended twice for its low accident rate.

The 477th’s training fell so far behind schedule that USAAF superiors ordered the unit be moved to Freeman Army Air Field near Seymour, Indiana. Not only was an additional move disruptive to the training schedule, but airmen and their families were the victims of a highly prejudice civilian population, especially during the times they left the confines of Freeman.

Finally, in April 1945, Selway’s segregation policies and the unit’s failure to become combat ready reached a boiling point among many of the African American airmen under his command. According to records, Selway’s commanding officer, Major General Frank Hunter, perceived his role as the Commanding Officer to do everything possible to deny the Tuskegee Airmen opportunity to enter the combat theater and prevent them from gaining any respect as leaders.

Selway’s own actions at the recommendation of his commanding officer, African American officers were forbidden to enter the base’s Officers’ Club and other facilities maintained for white airmen. The situation reached a boiling point on April 5th and days following when African American officers entered the Club despite Selway’s orders to stay out or face arrest. By April 7th, sixty African American officers were placed under house arrest.

On April 9th, Selway attempted to deny the African American officers access to the Club be redesignating access to the Club by restricting access based on assignment classifications knowing that no African American airmen held that designation. In addition, Selway issued a written order and required the signatures from all of the white and African American officers assigned to the base. Approximately 101 African American officers refused to sign the order. The group was threatened with a court martial for “willful disobedience” and given another opportunity to sign the order. None of the airmen signed the order.

Selway was ready to reopen the Club under a new designation when he learned that 100% of the African American personnel were going to attempt enter the Club. Later that evening, Selway observed African American officers near the Club, but they never violated any base regulations.

Eventually, the matter came to national attention and the NAACP supported the officers involved in the matter. After a review by Army officials, including the Commanding General of the Army Air Forces only the three officers who on April 5th were the first to violate the order were brought to trial. The Air Corps Judge Advocate General ordered the three officers be released. After hearing the matter, the court ruled that the Selway’s original order was in violation of Army Regulations which left the court with no other verdict, but to find the three officers innocent of the charge. However, one officer had an additional charge for shoving the provost marshal during the incident. The officer was found guilty and fined $150.

In May 1945, General Arnold replaced all of the white officers for the 477th and appointed Colonel Benjamin Davis, Jr. as the commanding officer of the African American units which included the Fighter Groups and Bombardment Groups. Sadly, by the time the issues involving Selway’s orders were resolved, Allied Forces were well on the way to ending the War in Europe and only months away from the end of the War against Japan.

Despite their fight against institutional racism, the Tuskegee Airmen were able to distinguish themselves as they battled the Axis Powers over the skies of the Mediterranean and Europe.

By the completion of World War II, the Tuskegee Airmen accumulated the following record of accomplishments:

Awards and commendations:

Three Distinguished Unit Citations:

99th Pursuit Squadron for their actions over Sicily.

99th Fighter Squadron for air strikes at Monte Cassino

332nd Fighter Group for the bomber escort mission to Berlin.

At least (1) Silver Star

(96) Distinguished Flying Crosses to 95 airmen.

(14) Bronze Stars

(744) Air Medals

At least (60) Purple Hearts

Enemy Causalities:

1578 combat missions: 1267 with the Twelfth Air Force; and 311 with the Fifteenth Air Force.

112 enemy aircraft destroyed in the air, 150 on the ground, and 148 damaged.

950 rail cars destroyed

40 boats or barges destroyed

The actions of Tuskegee Airmen put to rest the assertions that were brought forth in the 1925 Memorandum issued by U.S. Army Commandant, H.E. Ely. They unquestionably demonstrated they were not only willing to serve in the defense of our country, but their aviation skills were second to none.

As a result, of the success of the Tuskegee Airmen, doors began to open in many ways. In 1948, the once junior Senator from Missouri, Harry S. Truman, whose chance meeting with two African American aviators led to the creation of the Tuskegee Airmen, was now the 33rd President of the United States and he signed into law, Executive Order 9981, which banned segregation practices in the U.S. military. Decades later political and military leaders, agreed to provide women of all ethnic and racial backgrounds in our armed forces the ability to serve in combat roles, including that of aviators.

The Back Story

When I set out to write this story, I soon realized I could not truly tell the story of the Tuskegee Airmen without finding a source that could bring their story to life. I approached a contact at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum to see if she knew of a credible source that would be willing to assist me. Within days of my inquiry, I was contacted by Chauncey Spencer II, the son of the African American aviator discussed in this article.

Since his retirement, Spencer II with the assistance of the National College Resources Foundation (NCRF), has established the “History of Flight” mobile museum. Using a converted eighteen-foot Air Stream trailer and a pick-up truck, Spencer II travels the nation visiting schools, air museums, aviation conventions and other gatherings of interested audiences highlighting the contributions African American men and women have made to our nation’s aviation’s history.

As a child, Spencer II was able to not only hear his father’s stories, but he reflects on the many historic figures that actually visited with his father and family. With his memories as a starting point, Spencer II has expanded his knowledge through research and interactions with other sources.

During his presentations, Spencer II highlights that a majority of Americans young and old know about white aviation heroes such as Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhartt, and others. However, as time has passed, we have lost sight of the African American aviators who have not only had a positive impact on the African American community, but have also advanced achievements in the aviation field.

Not only is this important for us to understand our nation’s history, but Spencer II states that African Americans and other minority groups are underrepresented in the aviation and space field. He is constantly reminded of this during his visits to a variety of elementary, high school and college campuses throughout the year. Many of the students he talks with may be aware aviation and our space program, but very few have considered pursuing the opportunities available to them in these fields.

He encourages students at every level not to pass up opportunities to pursue Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) courses. For the elementary and high school students these courses lead to college and for college students these courses lead to degrees in fields that provide an endless number of employment opportunities.

In addition to his presentations, Spencer II and the NCRF have sponsored the production and installation of the statues highlighting the accomplishments of the Tuskegee Airmen including those of his father, Chauncey Spencer I. Currently, these statues are located at the Detroit City Airport, Palm Springs Air Museum, and in 2024, the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. The statue that has filled Spencer II with the greatest amount of pride is the recently unveiled statue of his father, Chauncey Spencer Sr. at the Lynchburg Regional Airport. Spencer II exclaims that it was exactly one hundred years ago that his father approached the Airport Manager and was denied access to flying lessons. Yet, his father did not let this setback stop him from following his dreams and in the end, he became a part of aviation history, and through his efforts, he opened doors for the generations to follow.

Spencer II states, “I decided to be a voice for those whose shoulders we all stand on so that nobody’s legacy will be left behind. There will always be the next generation to continue that history, and it will be the voice of the past in order to build a better future.”

Steve Tabor Bio

This South Bay native’s photographic journey began after receiving his first 35 mm film camera upon earning his Bachelor of Arts degree. Steve began with photographing coastal landscapes and marine life. As a classroom teacher he used photography to share the world and his experiences with his students. Steve has expanded his photographic talents to include portraits and group photography, special event photography as well as live performance and athletics. Steve serves as a volunteer ranger for the Catalina Island Conservancy and uses this opportunity to document the flora and fauna of the island’s interior as well as photograph special events and activities.

Watch for Steve Tabor Images on the worldwide web.