Let Us Not Forget! The City of Torrance Honors Our World War II Internees and Their Sacrifices By Photographer and Contributor Steve Tabor

Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

In the mid to late 1930’s, the winds of war were rising. On the European continent Hitler continued his conquest and in the east Japan was expanding its empire with its invasion of China. On the home front, many Americans held to the ideology of isolationism, but there was little doubt that tensions were growing between the U.S. and Japan.

Coming out of the Depression, part of the U.S. population began leaning towards a socialist belief and developing a classless society. Some even went further in their political beliefs and embraced the Nazi ideology. As for Asian immigrants and their families, those on the west coast, were dealing with anti-Asian racism and suspicions about their allegiance to the U.S. as many continued practicing their ancestral ceremonies and culture.

As a matter of national security, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, felt the need to summon the assistance of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to step up its surveillance of possible espionage and other subversive activities conducted by individuals and certain groups especially those who may be sympathetic towards Axis powers, Germany, Italy and Japan. In addition, U.S. government officials suspected that the German and Japanese governments were using Central and South American countries as staging areas for their spy corps, so the FBI sent agents to foreign embassies in those countries as diplomatic liaisons to monitor the activities of those suspected individuals.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt Courtesy of the National Archive and Records Administration

Within hours of the bombs dropping on Pearl Harbor, using the label of “enemy aliens” the FBI rounded up 1,212 individuals of Japanese ancestry and 559 individuals of German and Italian ancestry and placed the in the custody of them U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). The U.S. also pressured Central and South American governments to extradite 2,264 individuals of Japanese ancestry to the U.S. By 1942, the DOJ had over 4,000 “enemy aliens” in custody.

USS Arizona during Pearl Harbor Bombing Courtesy of the National Archive and Records Administration

The DOJ housed these individuals in detention centers located across the U.S. and supervised by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). In the Los Angeles area, centers were located in San Pedro, Griffith Park and Tujunga. Other west coast centers were located in the San Francisco Bay area, and Seattle.

Tuna Canyon Detention Station Photo by M.H. Scott, Officer in Charge, Tuna Canyon Detention Station. Courtesy of David Scott and the Little Landers Historical Society

Detainees were interrogated at these centers before being sent to DOJ camps in Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota and Texas. Generally, male and female detainees were housed separately except at the camps in Crystal City, Texas and Seagoville, Texas. At those camps, some families were housed along with single women.

Despite the FBI’s internment of “enemy aliens,” suspicions still surrounded many individuals of Japanese ancestry. Lobbyists, especially from western states, pressured Congress and President Roosevelt to take formal action against the entire population of those individuals, including those who were citizens of the U.S., by removing them from their homes and businesses and relocating them to the interior sections of the U.S.

During the congressional hearings, DOJ representatives raised constitutional and ethical objections to the proposal. So, it was determined that the U.S. Army would be designated authority to enforce any such action.

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order (EO) 9066, which divided the west coast of the U.S. into military zones. In addition, without designating any specific ethnic group, allowed the commanders of each zone to exclude individuals from that zone. Under the authority of EO 9066, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, Western Defense Command announced curfews specifically targeted against individuals of Japanese ancestry.

Lt. General John L. DeWitt Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

There were discussions among federal officials and western state government officials about relocating individuals of Japanese ancestry from the coastal areas and allowing them to live in the interior of the western states and using them as farm workers . Some expressed their concerns for the personal safety of the Asian population as reports of U.S. service members causalities were made known to their community members. Others voiced their deep seated in anti-Asian sentiments and insisted that individuals with Japanese ancestry should be placed in “concentration camps” regardless of their citizenship status.

On March 18, 1942, President Roosevelt signed EO 9102 which established War Relocation Authority (WRA) and was tasked with establishing and overseeing concentration camps. Concentration camps were constructed in remote areas of Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming.

U.S. Map showing the locations of the Detention Centers, Concentration Camps, and Other Camps.

At first DeWitt attempted to evacuate the individuals of Japanese ancestry from a limited number of areas on a voluntary basis. But, on March 19, 1942, under the authority of the EO 9102, DeWitt felt it was necessary to issue Public Proclamation No. 4, which called for the forced evacuation and detention of individuals with Japanese ancestry within 48 hours of receiving notice.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration Photo by Dorothea Lange

As the evacuation began, individuals and families were forced out of their homes and businesses and were only allowed to bring a small amount of their possessions to the camps. Prior to their internment, most were forced to sell their homes, businesses, and possessions well below market value to more than willing buyers not of Asian ancestry , leaving the internees with nothing to come home to at the conclusion of the war. Fortunate families found sympathetic friends who were not in danger of internment, to take care of their homes and possessions and in some cases their businesses during their internment period.

Store front in Little Tokyo prior to the evacuation Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Initially the detainees were sent to “assembly centers” under the direction of the Wartime Civilian Control Administration (WCCA). Internees were temporarily sent to Santa Anita Race Track and other locations along the west coast where they were processed and remained until permanent housing was available at one the WRA internment camps.

Ms. Lily Okuru poses with a statue of “Seabiscuit” at Santa Anita Assembly Center Photo by Clem Albers Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Within six months of the Proclamation, 122,000 individuals were removed from their homes placed in the custody of the U.S. Army. For the 70,000 detainees that were American citizens, the government did not bring any charges against them. There were several attempts to appeal the detainment of these U.S. citizens heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, but the Court upheld the Government’s position and the detainees remained under the custody of the U.S. Army until the conclusion of the war.

Harry Konda leaves the quarters of the Japanese American Citizens League in Centerville, CA Photo by Dorothea Lange Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration

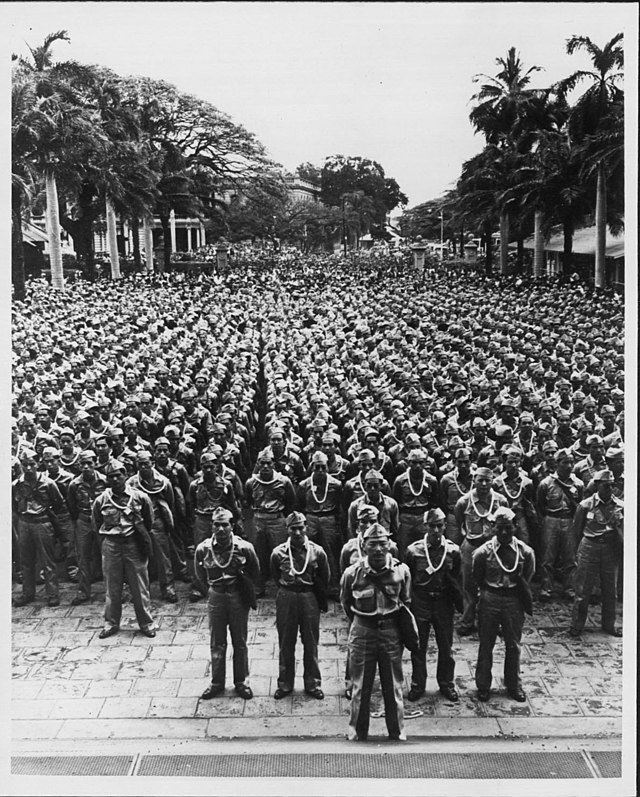

Despite their detention, some 30,000 Japanese Americans expressed their patriotism and volunteered to serve in segregated units in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War II. In the European theatre, the 18,000 men of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team distinguished themself as the most decorated unit for its size and length of service in the history of the U.S. military. The unit earned seven Presidential Unit Citations, 21 Medals of Honor, and approximately 4,000 Purple Hearts.

Members of the 442nd at Iolani Palace prior to their departure for training Photo by Nika Nashio Courtesy of the Hawaii State Archives

Following the War, the detainees were released and allowed to return home or relocate. The individuals that had jobs in their camps had a small amount of money to use to begin anew. Some were able to reestablish themselves in their communities because their non-interned friends maintained their property and businesses while they were interned. But, for most they had nothing to come home to and needed to start over.

According to 1983 calculations, detainees lost an estimated $1.3 billion in property and a net income loss of $2.7 billion. In 1948, the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act provided small reimbursements for property loss. In 1988, Public Law 100-383 acknowledged the injustice of incarceration and issued an apology along with a $20,000 payment for each incarcerated individual.

President Reagan signs Public Law 100-383 Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

It is his detainment and the detainment of others like him that has sparked the dream of the 90-year-old concentration camp survivor, Kanji Sahara, to honor those who were unjustly incarcerated and to remind future generations that this action cannot be allowed to be repeated.

Kanji Sahara

As a result, Sahara and his other Executive Board members formed the non-profit organization, World War II Camp Wall (WWIICW). With a $5 million grant from the State of California, the City of Torrance in collaboration with the WWIICW will erect a monument memorializing all of the individuals who were detained by DOJ and held in the WRA concentration camps at Columbia Park in the City of Torrance.

Sahara originally had the vision of the monument when discussions were held regarding the construction of a Peace Park at the site of Tuna Canyon Detention Center. When plans for the park failed to materialize, Sahara began seeking other possible locations for the monument and possible funding sources.

WWIICW Board President, Nancy Hayata, states, “Sahara developed his dream in 2017. We started meeting with several local government and state level leaders discussing possible funding sources and locations for the monument. During our discussions, we emphasized a memorial or monument honoring these individuals does not exist anywhere in our country and it is important to remember the sacrifices and injustices these individuals faced.”

Kanji Sahara and Nancy Hayata

Hayata remembers meeting Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi, who represents the beach cities from El Segundo to Redondo Beach, the Cities of Torrance, Gardena, Lomita and the Palos Verdes Peninsula. Muratsuchi was extremely interested in the project and identified a possible State funding source. When the grant was drafted, Muratsuchi made certain that the City of Torrance was designated as the monument’s location.

The WWIICW Executive Board along with their Community Liaisons, and Members at Large, who include former City of Torrance Mayor, Patrick J. Furey, thought the City of Torrance would be a suitable location for the monument. Several Torrance locations were discussed with Torrance officials, but Columbia Park, home of the annual Cherry Blossom Festival, seemed best suited as home of the monument.

The monument will be situated near the corner of 190th Street and Prairie Ave., which is near the cherry blossom trees and easily accessible to visitors. Prior to the COVID-19 shutdown, the design and site engineering work were originally performed pro bono by architect, Gregg Maedo and Associates and Sandra Ichiho, an Operations Manager for Hensel Phelps Construction Co.

Following the shutdown both were overwhelmed with a backlog of work and unable to continue to dedicate their time performing additional work on the monument. Assemblymember Muratsuchi advised the WWIICW Board to speak with architect Roger Yanagita. Yanagita agreed to assist pro bono. Among his tasks were: creating necessary detail drawings and plans; updating cost estimates; and per the request of City officials, inserting an additional restroom facility.

Architectural rendering of the monument near the corner of 190th Street and Prairie Avenue

The monument will consist of 12 black reflective granite walls 5 feet wide and 8 feet tall that will be placed diagonally along the triangular cement pad. The names of the detainees will be placed on the wall according to the camp where they remained during the war. Hayata explains, “Although there were approximately 120,00 detainees, we will have 160,000 names on the walls because some individuals resided in multiple camps during the detention period.”

Site plan showing the location of monument at Columbia Park

Assisting with developing an accurate list of detainees is Dr. Duncan Williams, director of the Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religion and Culture at the University of Southern California (USC). Dr. Williams has created a web-based memorial honoring detainees of Japanese ancestry consisting of approximately 125,000 names. Currently he is working to correct the spelling of names and adding any of the names of individuals who were not previously listed in the database. Dr. Williams has agreed to share his database to ensure the monument reflects the most accurate record of those individuals incarcerated at the camps.

In addition to his work on the database, Dr. Williams developed the Ireichō or “Book of Names”, living document that is the most comprehensive and accurate listing of every individual of Japanese ancestry that was incarcerated in the concentration camps during World War II. The book is currently on display for public review and acknowledgement of the individuals listed in the document at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM).

Also, in collaboration with the project, Dr. Russell Endo, a retired professor at the University of Colorado (UC), is compiling a list of approximately 2,000 names of German, Italian, and Peruvian Japanese individuals who were held at the Tuna Canyon Detention Station.

Hayata anticipates the groundbreaking ceremony for the project will be conducted sometime this summer. If all goes as planned, the project will be completed in two years. Hayata estimates that it will take approximately 1½ years to obtain the names of the detainees on the walls.

In the future, the WWIICW hopes to incorporate educational display panels next to the granite walls telling the story of the incarceration and the injustices the detainees faced, in hopes that it will inspire visitors to never forget and never allow something like this to happen again.

Hayata, like all of the members of the Executive Board, Community Liaisons, and Members at Large, are all volunteers and continue to dedicate their personal time to create this tribute. When asked what motivates Hayata to take on such a project, Hayata responds, “Our motivation comes from Sahara himself. Working with him almost daily, you can see in his eyes what it means to accomplish such a project that honors the sacrifices that so many made and how it impacted on their lives. You can easily see the joy it brings to him to make this dream a reality and his joy inspires us all.”

Nancy Hayata

The WWIICW is seeking individual and community donations to assist with the monument, display panels and educational programs. Interested parties can contact the WWIICW at

WWIIcampWall@gmail.com or by visiting www.wwiicampwall.org.

Want to Learn More about the Internment

Visit the Japanese American National Museum Exhibit, “Don’t Fence Me In-Coming of Age in America’s Concentration Camps.” The exhibit runs through October 1, 2023.

The Japanese American National Museum is located at 100 North Central Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90012. For more information visit www.janm.org.

Steve Tabor Bio

This South Bay native’s photographic journey began after receiving his first 35 mm film camera upon earning his Bachelor of Arts degree. Steve began with photographing coastal landscapes and marine life. As a classroom teacher he used photography to share the world and his experiences with his students. Steve has expanded his photographic talents to include portraits and group photography, special event photography as well as live performance and athletics. Steve serves as a volunteer ranger for the Catalina Island Conservancy and uses this opportunity to document the flora and fauna of the island’s interior as well as photograph special events and activities.

Watch for Steve Tabor Images on the worldwide web.