Hometowns to Hollywood: Myrna Loy By Annette Bochenek, Ph.D.

Being a fan of Art Deco, I am often drawn to Myrna Loy and the many films in which she starred, as so many of her screen portrayals were in front of beautiful Screen Deco backdrops. Additionally, she was the perfect sidekick to William Powell throughout their many on-screen pairings, equipped with a wry wit shrouded in glamour.

Loy was born Myrna Adele Williams in Helena, Montana, to Adelle Mae and rancher David Franklin Williams. Loy’s first name was derived from a whistle stop near Broken Bow, Nebraska, whose name her father liked. She was raised in nearby Radersburg, along with her younger brother, David. Her father was also a banker and real estate developer and the youngest man ever elected to the Montana state legislature. Her mother studied music at the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago.

During the winter of 1912, Loy’s mother was seriously ill with pneumonia, so her father sent his wife and daughter to La Jolla, California. While recovering, Loy’s mother saw great potential in Southern California, and during one of her husband’s visits, she encouraged him to purchase real estate there. Among the properties he bought was land he later sold at a considerable profit to none other than Charlie Chaplin, so the filmmaker could construct his studio there. Although her mother tried to persuade her husband to move to California permanently, he preferred ranch life and the three eventually returned to Montana.

Soon afterward, Loy’s mother needed a hysterectomy and insisted Los Angeles was a safer place to have it done, so she, Loy, and Loy’s brother David moved to Ocean Park. Loy began taking dancing lessons while her mother had her procedure and was undergoing recovery. After the family returned to Montana, Loy continued her dancing lessons, and at the age of 12, Myrna Williams made her stage debut performing a dance she had choreographed based on “The Blue Bird” from the Rose Dream operetta at Helena’s Marlow Theater.

Tragically, Loy’s father died on November 7, 1918, of Spanish influenza. Upon his passing, the family permanently relocated to California, where they settled in Culver City. Loy attended the exclusive Westlake School for Girls in Holmby Hills and continued to study dance in Downtown Los Angeles. When her teachers objected to her participating in theatrical arts, her mother transferred her to Venice High School, and at 15, she began appearing in local stage productions. Loy was a good student with high grades and teachers remembered her as quiet, unassuming, talented, and lovable.

In 1921, Loy posed for Venice High School sculpture teacher Harry Fielding Winebrenner for the central figure “Inspiration” in his allegorical sculpture group Fountain of Education. Completed in 1922, the sculpture group was situated in front of the campus outdoor pool in May 1923, where it would stand for decades. Loy’s slender figure with her uplifted face and one arm extending skyward presented a “vision of purity, grace, youthful vigor, and aspiration” that was singled out in a Los Angeles Times story that included a photo of the “Inspiration” figure along with the model’s name—the first time her name appeared in a newspaper. A few months later, Loy’s “Inspiration” figure was temporarily removed from the sculpture group and transported aboard the battleship Nevada for a Memorial Day pageant in which “Miss Myrna Williams” participated.

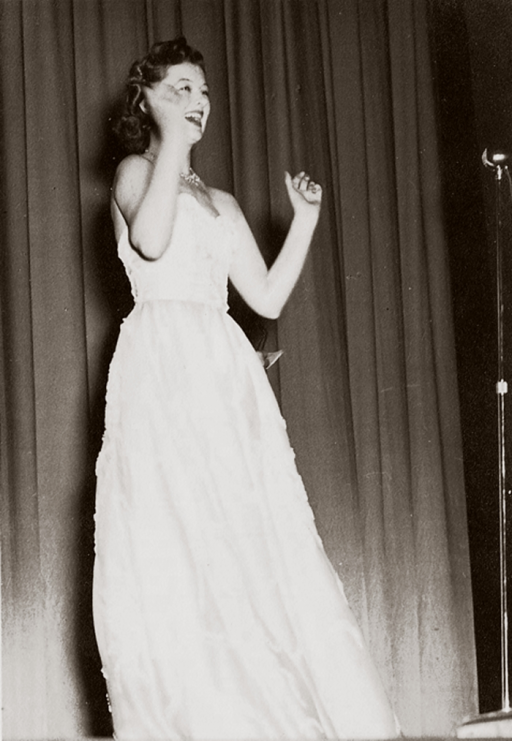

Loy left school at the age of 18 in order to help with the family’s finances. She obtained work at Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre, where she performed in elaborate musical sequences that were related to and served as prologues for the feature film. During this period, she saw Eleonora Duse in the play Thy Will Be Done, and the simple acting techniques she employed made such an impact on Loy that she tried to emulate them throughout her career.

Portrait photographer Henry Waxman had taken several pictures of Loy, and they were noticed by Rudolph Valentino when he went to Waxman’s studio for a sitting. He was looking for a leading lady for Cobra, the first independent project his wife Natacha Rambova and he were producing. Loy tested for the role, which went to Gertrude Olmstead, instead, but soon after she was hired as an extra for Pretty Ladies (1925), in which fellow newcomer Joan Crawford and she were among a bevy of chorus girls dangling from an elaborate chandelier.

Rambova recommended Loy for a small but showy role opposite Nita Naldi in What Price Beauty? (1925). Although the film remained unreleased for three years, stills of Loy in her exotic makeup and costume appeared in a fan magazine and led to a contract with Warner Bros., where her surname was changed from Williams to Loy.

Loy’s silent film roles were mainly vampish, and she frequently portrayed characters of Asian or Eurasian background in films such as Across the Pacific (1926), A Girl in Every Port (1928), The Crimson City (1928), The Black Watch (1929), and The Desert Song (1929), which she later recalled “kind of solidified my exotic non-American image.” It took years for her to overcome this stereotype, and as late as 1932, she was cast as a villainous Eurasian in Thirteen Women (1932). She also played, opposite Boris Karloff, the depraved sadistic daughter of the title character in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932).

Prior to that, Loy appeared in small roles in The Jazz Singer and a number of early lavish Technicolor musicals, including The Show of Shows, The Bride of the Regiment, and Under a Texas Moon. As a result, she became associated with musical roles, and when they began to lose favor with the public, her career went into a slump. In 1934, Loy appeared in Manhattan Melodrama with Clark Gable and William Powell. In fact, when gangster John Dillinger was shot to death after leaving a screening of the film at the Biograph Theater in Chicago, the film received widespread publicity, with some newspapers reporting that Loy had been Dillinger’s favorite actress.

After appearing with Ramón Novarro in The Barbarian (1933), Loy was cast as Nora Charles in the 1934 film The Thin Man. Director W. S. Van Dyke chose Loy after he detected a wit and sense of humor that her previous films had not revealed. At a Hollywood party, he pushed her into a swimming pool to test her reaction, and felt that her aplomb in handling the situation was exactly what he envisioned for Nora. Louis B. Mayer at first refused to allow Loy to play the part because he felt she was a dramatic actress, but Van Dyke insisted. The Thin Man became one of the year’s biggest hits, and was nominated for Best Picture. Loy received excellent reviews and was acclaimed for her comedic skills. Her costar William Powell and she proved to be a popular screen couple and appeared in 14 films together, one of the most prolific pairings in Hollywood history. Loy later referred to The Thin Man as the film “that finally made me… after more than 80 films.”

Her successes in Manhattan Melodrama and The Thin Man marked a turning point in her career and she was cast in more important pictures. Such films as Wife vs. Secretary (1936) with Clark Gable and Jean Harlow gave her opportunity to develop comedic skills. She made four films in close succession with William Powell: Libeled Lady (1936), which also starred Jean Harlow and Spencer Tracy, The Great Ziegfeld (1936), in which she played Billie Burke opposite Powell’s Florenz Ziegfeld, the second Thin Man film, After the Thin Man with Powell and James Stewart, and the romantic comedy Double Wedding (1937). She also made three more films with Gable.

By this time, Loy was highly regarded for her performances in romantic comedies and she was anxious to demonstrate her dramatic ability, and was cast in the lead female role in The Rains Came (1939) opposite Tyrone Power. She filmed Third Finger, Left Hand (1940) with Melvyn Douglas and appeared in I Love You Again (1940), Love Crazy (1941), and Shadow of the Thin Man (1941), all with William Powell.

With the outbreak of World War II, Loy all but abandoned her acting career to focus on the war effort and work closely with the Red Cross. She was so fiercely outspoken against Adolf Hitler that her name appeared on his blacklist. She helped run a Naval Auxiliary canteen and toured frequently to raise funds. She returned to films with The Thin Man Goes Home(1945). In 1946, she played the wife of returning serviceman Fredric March in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Throughout her career, she championed the rights of black actors and characters to be depicted with dignity on film. Loy was paired with Cary Grant in David O. Selznick’s The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947). The film co-starred a teenage Shirley Temple. Following its success, she appeared again with Grant in Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (1948), and with Clifton Webb in Cheaper by the Dozen (1950).

After 1950, Loy’s film career continued sporadically, appearing in occasional films. In 1965, Loy won the Sarah Siddons Award for her work in Chicago theatre. Additionally, she appeared in a handful of television roles. Her last motion picture performance was in 1980 in Sidney Lumet’s Just Tell Me What You Want. She also returned to the stage, making her Broadway debut in a short-lived 1973 revival of Clare Boothe Luce’s The Women. In 1981, she appeared in the television drama Summer Solstice which was Henry Fonda’s last performance. Her last acting role was a guest spot on the sitcom Love, Sidney, in 1982.

In later life, she assumed an influential role as co-chairman of the Advisory Council of the National Committee Against Discrimination in Housing. In 1948, she became a member of the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO, the first Hollywood celebrity to do so. Loy had two mastectomies, in 1975 and 1979, for breast cancer.

Her autobiography, Myrna Loy: Being and Becoming, was published in 1987. The following year, she received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Kennedy Center. Although Loy was never nominated for an Academy Award for any single performance, she received a 1991 Academy Honorary Award “for her career achievement.” She accepted via camera from her New York City home, simply stating, “You’ve made me very happy. Thank you very much.” It was her last public appearance in any medium.

Loy died on December 14, 1993, in a Manhattan hospital during unspecified surgery. She was 88 years old. She had been frail and in failing health. She was cremated in New York and her ashes interred at Forestvale Cemetery in her native Helena, Montana.

Helena still brims with Loy’s legacy, as several places of relevance to her still stand in the Helena area. First of all, Loy’s childhood home still stands at 507 5th Ave in Helena, Montana. It is in beautiful shape and is privately owned. In fact, while Loy was growing up there, one of her neighbors on this same street was also a future actor–Gary Cooper!

While Loy’s home still stands, the Marlow theater, in which she performed does not. The theater was razed to make way for a parking lot.

Before the theater’s demise, Loy did get a chance to see it again after she had established herself as a Hollywood actress. She returned to Helena for a visit in March of 1940, which included a stop at the Marlow Theater. Here, she received a bouquet of flowers from the mayor at the time.

In 1991, the Myrna Loy Center for the Performing and Media Arts opened in downtown Helena, not far from Loy’s hometown. Located in the historic Lewis and Clark County Jail, it sponsors live performances and alternative films for under-served audiences.

Loy’s legacy is still celebrated in California, where she spent her teenage years. Her legacy is most prominently featured with the restoration of the Loy statue for which she had posed prior to her fame.

While the statue had miraculously survived the 1933 earthquake, its story took a turn for the worse decades later. Over the years, the statue of Loy outside of Venice High School in Los Angeles became not only a landmark after Loy became famous, but an object of vandalism from neighboring schools, especially University High. It was customary prior to the Venice-Uni football game for students from Uni to throw paint on or otherwise vandalize the statue. When I was a student at Venice, legend had it that one year, a group of students from Uni actually removed the statue and drove it in a truck to Santa Monica pier where they threw it over the side and into the water.Not surprisingly, damage took its toll. At one point, the arms were reconfigured as a form of restoration. Finally about 20 years ago, the statue was removed and packed away in pieces. After decades of exposure to the elements and vandalism, the original concrete statue was removed from display in 2002. The defaced statue was replaced in 2010 by a bronze duplicate paid for through an alumni-led fundraising campaign during a highly-publicized ceremony.

The newly-restored statue in Los Angeles and various tributes to Loy in her beloved Helena stand as heartening tributes to a classy, brilliant beauty.

Bio:

Annette Bochenek, Ph.D. is an archivist, film historian, and avid scholar of Hollywood’s Golden Age. She manages the Hometowns to Hollywood blog, in which she profiles her trips to the hometowns of classic Hollywood stars. She also hosts a film series by the same name. She has been featured on Turner Classic Movies and is president of the Windy City Film Fanatics. A regular columnist for Turner Classic Movies, Classic Movie Hub and Silent Film Quarterly, her articles have also appeared in Nostalgia Digest, The Dark Pages Film Noir Newsletter, and Chicago Art Deco Society Magazine.